About

Faisal Abdu’Allah is an internationally acclaimed British artist who creates iconographic imagery of power, race, masculinity, violence, and faith to challenge the values and ideologies we attach to those images and to interrogate the historic and cultural contexts in which they originate.

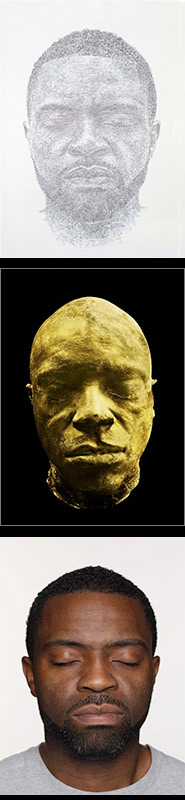

Trained as a printmaker, his work evolved out of the interface of photography, printed media, film, installation, and performance. His debut exhibition upon graduating from the Royal College of Art ‘I Wanna Kill Sam…’ (1993) quickly established his interest in confrontation and displacement through provocative installation pieces. He brokers disparate worlds through his practice, best exemplified in ‘The Garden of Eden’ (2003) with architect David Adjaye, ‘Gold Finger’ (2007) with the late Joey Pyle from the British Mafia and more recently ‘Double Pendulum’ (2011), an exploration of breathing through training rituals of sports athletes featuring British Olympian sprinter, Jeanette Kwakye.

Abdu’Allah was born in England to Jamaican immigrant parents, and was inspired to revert to Islam as an adult after spending time in the United States. In addition to being a Senior Lecturer in Fine Arts at the University of East London, he still occasionally cuts hair at his barber shop/studio in Harlesden, London, called Faisal's.

Abdu’Allah has participated in the Sharjah, Torino, and Tallinn Biennales and has been the recipient of the Decibel Artist Award 2005, Tallinn Print Triennial 2007, and IDA award 2010. He was a professor and artist in residence at Stanford in 2010, where he launched the touring exhibition 'The Art of Dislocation,' the largest retrospective of his work to date. In 2012 the exhibition traveled to the CAAM in Spain along with Magnolia Editions’ book of the same name.

Links

Faisal Abdu’Allah website

2008 interview in New Statesman

Audio slideshow of visit to Faisal Barbers, Guardian UK, Sep 2011

Essay

Published here with permission from Barbaro Martinez-Ruiz

The London in which Abdu’Allah was born and in which he matured as an artist was one marked by Margaret Thatcher’s tenure as prime minister and British art during [this] period was generally stunted by a conservative government that had little interest in or commitment to fund the arts. Anxiety in British society during the Thatcher government was largely precipitated by a period that saw the dissolution of Britain’s imperial world and its slip from a position of world economic dominance, together with […] significant demographic shifts. It was an era when artists, together with broader society, began to demand equal rights for minorities and more aggressively and openly began to put forth varied representations of social struggles taking place in a very class-oriented society.

The art of Abdu’Allah and his contemporaries in the early 1980s can be evaluated in a manner that fills an important void within available scholarship on the subject of contemporary art in relation to Afro-British culture. What began as an artistic gesture in the 1980s more fully materialized in the early twenty-first century as a complete conceptual approach that questioned issues of race and identity in relation to issues of cultural diversity and multiculturalism. Race, some have argued, while continuing to gird an important set of [arguments] in relation to understanding cultural formation and location, social history, political conscience, and memory of those transcendental historical moments, is no longer central. Instead, race becomes one of several contested areas of identity, which must be negotiated in society, including national identity, religious faith, and gender. Abdu’Allah’s work broke away from the British artistic establishment and the rules of institutional representation, particularly insofar as he began selecting his subjects from émigré utopia, Afro-British social consciousness, Muslim identity, and working-class life. He also integrated other views of London, portraying it as a city of dislocated communities that were powerless in the existing world of art.

The art of Faisal Abdu’Allah is, first of all, about de-materializing surfaces. Burning the paper, drawing lines to cover most surfaces, creating holes and building narratives around the resulting absence of material. An important step in Abdu’Allah’s artistic career was enrollment at the age of twenty in the Massachusetts College of Art. By the time he reached Boston he was a skilled communicator and very socially sensitive, attributes which proved essential for overcoming his initial cultural dislocation.

His early work during this period evidenced his training as a printmaker under professors Tony Martina at the Saint Martin School of Art and Tim Mara at The Royal College of Art, London and he speaks of the primary goal being “to exhaust the paper to its physical limit.”

This process, vital to his early work, would go on to form a core of his broader body of work, including the later-produced photography and multimedia projects.

The drawing ‘Paper Ends’ (1988-89), made during his final year at the London Royal College, is an abstract work and, as suggested by the title, is an example of dematerialization and the artist’s experience of a sense of nostalgia about losing a surface. Clearly highlighted with burn marks that spread out across the paper’s surface, creating high contrast between the white spaces between the burns and the shadows projected onto a second surface placed behind the first to create an optical illusion of depth and three-dimensionality. Right in front of our eyes such [an] act of destruction turns a sheet of paper into a new material form, an object that appears to be levitating. Abdu’Allah contrasts these white holes with almost calligraphic arabesque, evoking electric pulses coming out of the surfaces in a chaotic manner. This electric written style is very common among Pentecostal and Revival religious traditions in Jamaica, and Abdu’Allah’s father was an active Pentecostal priest at the time the drawing was made in London. In Revival churches, such electric writing is strongly associated with God’s pulsation, which manifests in an infinity zigzagging as a way to contain his vitality. Jamaican Pentecostal and Revival religious traditions have a strong connection with Central African forms of graphic expression seen throughout the Caribbean in which such writing represents the ancestors’ activities, a flawed graphic form that highlights imperfection while symbolizing their dignified strength. These and related types of electric writing have also been explored by the African American artist David Hammons in his 2004 drawing series ‘Spirit Writing.’

Abdu’Allah’s use of fire to burn the paper serves as a metaphor for death and alludes to the coming together of the ancestors. His attempt to cover the entire surface of the paper is a clear rejection of the horror of an emptiness in which color cannot stand in its own physicality. Abdu’Allah’s unusual treatment and reconsideration of surfaces extends beyond his drawings and is a marked characteristic seen across much of his photographic work. Opting to focus on a photograph’s physical qualities and materiality through the continued use of conventional (analog) photography, Abdu’Allah treats the photographic realm as a surface, as an object materialized by the photographic medium that can be treated in a manner similar to painting canvas.

His choice to mount and print on metal creates a three-dimensional existence and conveys narratives like video sequences. Abdu’Allah’s photographic gestures freed his photography from the concerns around the alleged death of photography in the face of the digital format and the attendant simplification of the photographic process, loss of autonomy due to diversification and heightened accessibility and high-speed consumption of photographic material via the Internet. Abdu’Allah’s work also creates a play on the physical apprehension of a printmaker, a painter or a filmmaker whose interest goes both beyond and within the representation on surfaces to express the role of an itinerant in society. The heavy use of multiple visual elements on a single surface seen in ‘Paper Ends’ is very similar to that of Abdu’Allah’s later prints, including ‘I Wanna Kill Sam…’ in which he uses aluminum plates in place of paper surfaces. Such surface material choice has been described as suggesting that the “bodies looks like they have been carved from marble.” As described by Bryan Wolf, Abdu’Allah’s use of aluminum plates made “the bodies look like they are being consumed by their own abstraction”, suggesting that the degree of pixilation of the print and the manner in which the depicted subjects were mirrored and multiplied by each individual portrait raised an ontological question about self-perception of the viewer.

The work self-devours and de-materializes its subjects, not merely as a result of the acid acting on the surface of the metal plates but in a more subtle way in which one can simultaneously visually experience being at one with the nature of the other figures depicted on the aluminum plates and encountering oneself through viewing life-size images. In other words, it invites a double understanding of oneself and the other.

Wolf went on to comment that “Abdu’Allah’s work makes you feel a sense of shame when you experience self inadequacy in understanding his subject, familiarity, and otherness within some visual resemblance and a sense of guilt experienced publicly.”

[This] comment alludes to the most striking feature [of] Abdu’Allah’s visuality, his creation of a sense of “disconcertment,” a state he uses to create and maintain in the viewer a sense of anxious embarrassment and unpleasant emotion. By juxtaposing an experience of moral incorrectness with the subjects he explores, such as racial stereotype, masculinity, cultural dialogism, [and an] iconography of violence, Abdu’Allah creates and plays upon a sense of remorse. In a 2010 letter, Abdu’Allah described some of his ideas behind this project:

"From the early beginnings in ‘I Wanna Kill Sam…’ I have always had an obsession with badness and the strand was evident in some key earlier works ‘Grave Diggaz,’‘Innocence Protects You,’ and ‘An Affair of Honour.’ All made some comment on morality, perception, and remorse about malevolence. But that was never enough for me and the desire to go to another level to fully comprehend malevolence was achieved through ‘Goldfinger’ (2007), a collaboration with the late East End mafia don Joey Pyle, looking at transformation utilizing the technical process of alchemy."

The images call to mind the idea of extended family practices among Caribbean communities in London and moral issues surrounding a community’s right to self-representation. Abdu’Allah, a member of [one] such Caribbean community, represents a paradigm in the vernacular domain of a culture heavily influenced by African-American popular culture that plays [a] critical role in the formation of Afro-British fashion identity. His images also share an iconographic trait with early Hollywood publicity of Western movies as well as with James Bond movie posters for the 1964 film ‘Goldfinger.’ His sharply spatial conception of the images […] mirrors the social concerns that imbue his work. The images represented through a collection of distinct pixels can reconstruct themselves, but only when seen from a distance, when the pixelated images become clear and the images operate in conjunction with one another. Similarly, the images can be understood as “re-materializing,” emerging from the act of dissolving the metal surface and reappearing in a new physical form.

Although Abdu’Allah’s series came out [of] his training as [a] printmaker and long use of the silk screen-printing process, there is a clear allusion to Andy Warhol’s series of portraits of Elvis Presley. Like Warhol’s Elvis series, Abdu’Allah’s ‘I Wanna Kill Sam’ series share an insistence on repetition that is a very common trait in Pop art visual strategy in relation to the vernacular culture, images of publicity and media. However, instead of using the same type of image as Warhol does, Abdu’Allah uses similar sized aluminum plates, but always containing a different portrait. A more striking difference between the two series is the visual principles underlying them. For Warhol repetition will always be better [than] one unique piece, [and] each repetition will be different from the original master print as a result of the imprecise printing process and human error […]. For Abdu’Allah repetition has more linguistic implications insofar as a similarly constructed image is varied within the consistent genre of portraiture, like the infinite richness and variety of language. Such repetition alludes to verbal differences, which raise […] issues of consistent concern to Abdu’Allah such as masculinity, the embodiment of blackness, the consumption of images of violence associated with black imagery in the media and issues of memory in which the individual prints articulate moments of his relationship with the people portrayed.

Metaphor is frequently a subject of Abdu’Allah’s work. Instead of providing graphic accounts of violence and political distrust, Abdu’Allah’s photographs of violence are more direct social commentaries, a paradoxical response in which the violence produced by nature becomes a metaphor for political violence. Similarly, in this piece, he confronts the viewer with death as simply a human experience, yet one that cannot be fully understood until “you experience the passing of someone really close to you.”

Bárbaro Martínez-Ruiz

Director of Orbis Africa Lab

Art & Art History Department

Stanford University